1932: Dog Racing Gets on Track in El Cerrito

By Jon Bashor

This article first appeared in The Forge (December 2025), viewable here.

Race fans fill the stands at the El Cerrito Kennel Club track in this undated photo. EC Historical Society collection.

At 8:15 p.m. on Saturday, Oct. 22, 1932, a new era in nighttime entertainment opened as Sue Fulton, Hughminnia, Prairie Foe, Berta, Ford 8, Bona Fide, Over & Over and Lady Gog chased a speeding mechanical rabbit for 3/16 of a mile (330 yards) around a new track built specifically for greyhound racing.

“The El Cerrito Kennel Club, of El Cerrito, Calif., presents to greyhound racing followers what experts declare to be the finest and most modern plant in the United States, both in point of comfort and equipment,” read the introductory paragraph in the opening night program. “The track manager will be Mr. George F. Chapman of San Francisco who has held similar positions at prominent tracks in the country. His integrity is of the highest among followers of the sport.”

In his 1977 book “El Cerrito: Historical Evolution,” Edward Staniford wrote “The racetrack was a stellar attraction of the Bay Area drawing clientele from as far away as Los Angeles and Reno.”

The track, with a grandstand that could easily hold 3,000 fans, put El Cerrito in the same league as Emeryville (the first in the state), San Pablo, Menlo Park, San Bruno, South San Francisco, Alviso, Union Park and Bayshore City. When the El Cerrito Kennel Club was finally forced to shut down in 1939, it was the last dog track standing in California.

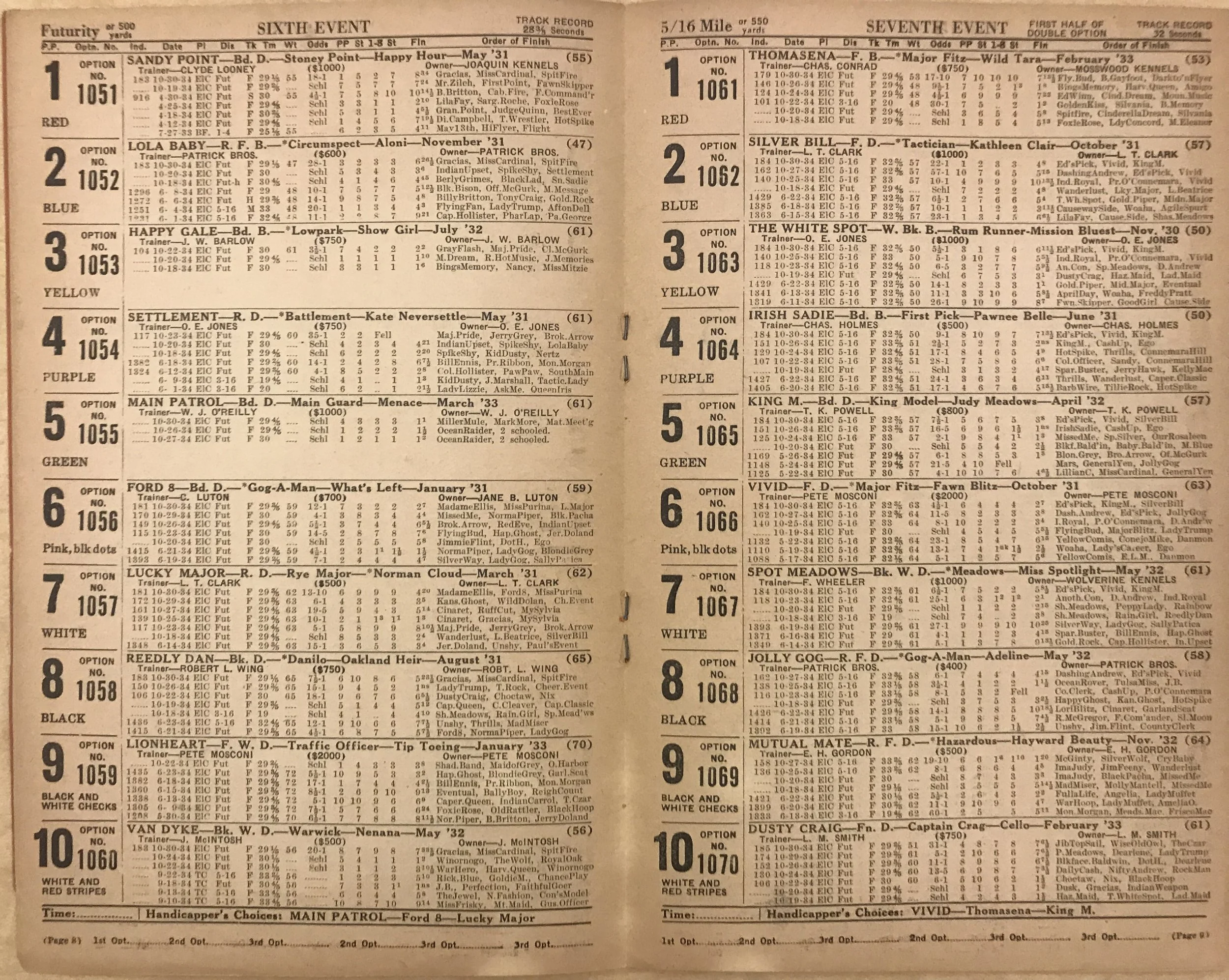

For seven years, the dogs were running in eight to 10 races six days a week around the quarter-mile oval. Races ranged in distance from 330 to 500 to 550 yards. Before each race, fans could peruse details about each of the competitors based on their past performances.

Each evening’s program listed details of the racers in every event. EC Historical Society collection.

“Greyhounds racing under the rules of the El Cerrito Greyhound Breeders’ Association are carefully classified and graded, and their record printed in the program for the prospective purchaser or option holder to buy,” according to a guide printed in the programs. “Anyone studying this information may easily judge the probable performances of the different greyhounds.”

But at the time, betting on races was illegal, so the dog and horse racing track operators created a loophole a full-grown greyhound could run through. The key word was option. Rather than placing bets, racing fans could purchase options on their favorite dog. If their pick did well, the fans could redeem their option for the stated purchase price published in the evening program. If not, they lost their investment.

“Any person in good standing upon the turf may buy an option to claim, pursuant to the claiming rules of the El Cerrito Greyhound Breeders’ Association, any dog at the price for which it is entered, which price is printed upon the program,” the program noted.

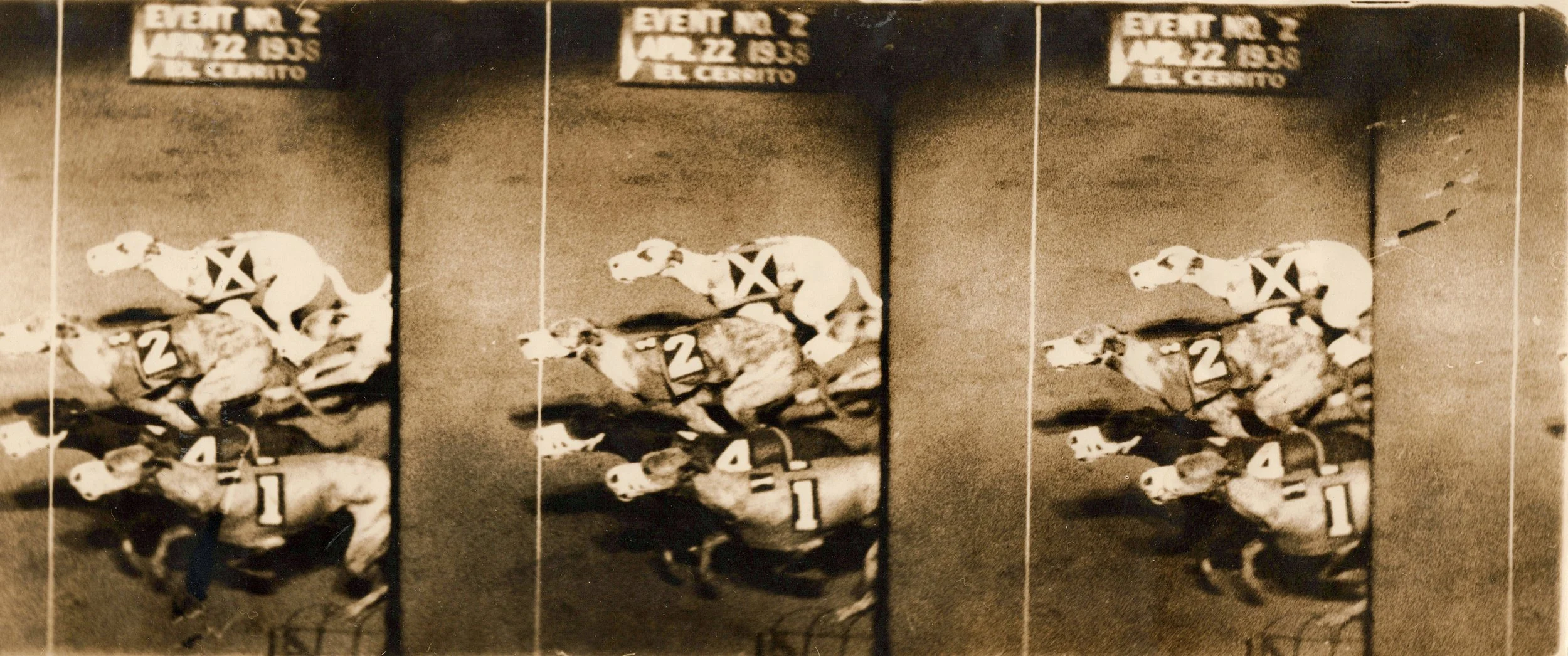

It's a photo finish as the first three dogs cross the finish line in the second race on April 22, 1938. EC Historical Society collection.

On the track

The track was located south of Fairmount Avenue between San Pablo Avenue and the Santa Fe Railroad right-of-way (where today’s BART tracks are located), placing it on the current site of the El Cerrito Plaza shopping center. Some street maps of the era included the “Dog Race Track” location. When construction started, the land was used as pasture adjacent to the rundown Castro Adobe.

Prior to each race, a grand marshal marched along the track to the starting gate. Behind him came the hounds, each accompanied by a uniformed groom. The racers were led into a “stall starting box, the most popular of all systems…instead of the strap method which causes much confusion at many tracks,” according to the opening night program. The track boasted that it used the Heintz Starting Box, which offered a number of advantages to both the track operators and the greyhounds.

Grooms parade with their greyhounds prior to a race. Photo EC Historical Society collection.

The rabbit chased by the dogs sped around the track at about 35 mph. According to the program, “The inside rabbit will also be used, preferable to most of the owners.”

However, the program also stated “If any mishap occurs during the running of a race, due to fault of mechanical devices, it will be declared no race and will be run over or declared off at the discretion of the Presiding Judge.”

But wait, there’s more!

Although photos show the grandstands to be mostly filled, the El Cerrito Kennel Club also offered special events and giveaways to draw in race fans.

Advertisements in the Richmond Independent touted ostrich racing, in addition to the dogs. One ad touted ostriches racing against horses, calling it “The Sensation of the Age” and claiming it to be “First Time on Any Track.”

For the track’s third anniversary in 1935, the management offered free gifts to racegoers. “Each Lady is presented with a Beautiful Compact. Each Gentleman is presented with a Pebble Beach Tie.” The program was expanded to 11 races for the occasion and a wrestling match was added as a bonus.

Ads in the Richmond Independent newspaper touted extra enticements to head to the track. EC Historical Society collection.

Another newspaper ad promised “Pretty Girl Jockeys Ride the Famous Racing OSTRICHES” and as added inducements stated a New Plymouth Sedan would be given away and invited attendees to “Enjoy our Luxurious Heated Clubhouses.”

And to top off the program, racegoers would “See the Hollywood MONKEY JOCKEYS ride the greyhounds.” In reality, the monkey jockeys, clad in jockey silks, were actually from Van Nuys in southern California.

The ‘Hollywood Monkey Jockeys’ were dressed in jockey silks and used the dogs’ blankets as saddles with pockets added to the hold the riders’ legs. EC Historical Society collection.

How it all started

According to a May 2, 1993 column by Nilda Rego in the West County Times newspaper, John “Blackjack” Jerome submitted an application, under the name Wembly Amusement Corp., to build the track to the El Cerrito City Council, offering to hire local residents to build and run the track. The offer to provide new jobs to local residents persuaded the council to approve the measure 3-2.

And, indeed, locals were hired, about 200 in all. That tally included El Cerrito City Councilman Philip Lee, who got a job as track superintendent, Rego reported. Mayor J. E. Beck was the traffic manager and Police Chief Ray Cheek and four of his officers were hired as security guards.

El Cerrito historian Mervin Belfils also described another opportunity: “Kids would go over the parking lot area picking up empty whiskey flasks the next day after the races and sell them to local bootleggers who purchased them for a few cents each which were used for re-filling purposes.”

Jerome had earned his reputation as a tough guy strikebreaker in Denver, Los Angeles and Oakland, and earned his nickname for his sidearm of choice: a blackjack, a short, flat leather truncheon filled with lead that could be hidden in a side pocket. His enforcers at the track ensured that bettors paid off their debts, Rego wrote.

Until he arrived, gambling in El Cerrito was mostly confined to dice and card games in the back rooms of restaurants and bars along San Pablo Avenue, as well as in Chinese restaurants located in “no man’s land,” an unincorporated area west of San Pablo Avenue, according to Rego’s column.

For her column, Rego interviewed Joe Staley of Pinole, whose father was a carpenter who helped build the grandstand. At age 20, Staley got a job in the ticket booth, selling tickets to busloads of race fans.

“They’d just swamp me in the ticket booth. I think it cost 50 cents to get in,” he told Rego. “I never gambled, but those races were something to see. Those dogs really stretched out after that rabbit, never caught it.”

Staley also recalled a fatal incident at the track when a young man “got on the track and somehow the mechanical rabbit got turned on. It went pretty fast, a long metal arm, hit him, killed him.”

An article in the Oct. 18, 1935 Oakland Tribune identified the victim as 22-year-old Harry Riley, “crushed to death when struck by the car carrying the mechanical rabbit.”

Local street maps included the location of the dog track just north on the Alameda/Contra Costa County line. EC Historical Society collection.

The downside

Staley also told Rego about another problem stemming from the track:

“Fleas. There was an epidemic of fleas. Every night grooms would walk 10 or 12 dogs at once on a leash through town,” Staley said. “Everybody got fleas, hard to believe now. When I went to bed during the summer, I had to pick them off me.”

On a larger scale, the opening of the track provided an opening for other, larger gambling operations in the area.

William “Big Bill” Pechart, who had Nevada connections, built the Wagon Wheel on Panhandle Boulevard (both have been renamed – today it’s the Eagles Lodge on Carlson Boulevard) near the intersection of Central Avenue. In his book, Staniford described the Wagon Wheel as a “first-rate gambling casino with a potpourri of chance games, slot machines, cards and dice.” It also housed a repair shop servicing up to 5,000 gambling machines from throughout the Bay Area.

Also in the 1930s, Pechart renovated the Castro Adobe and launched the Rancho San Pablo restaurant and nightclub, calling it “Showplace of the West” and featuring the Rancho Revue of comedy, song and dance. Located adjacent to the dog track, the Rancho also offered gambling.

The track was located south of Fairmount Avenue and southwest of Harding Elementary School (shown center left). The Castro Adobe is in the lower left corner. EC Historical Society collection.

The end of an era

In the 1930s, the state legislature twice passed laws to legalize dog race betting, but both were vetoed by then-Governor Frank Merriam.

Newly elected California Attorney General Earl Warren, who would later be elected to three terms as governor and was appointed chief justice of the United States in 1953, disapproved of gambling on greyhound races and was determined to shut down the tracks. According to an article in the Journal of the Emeryville Historical Society, Warren claimed that the races attracted low-income bettors who couldn’t afford it and had no protection when track owners rigged the odds.

“...race track owners had operated the tracks in defiance of the law ever since their spread to California some years ago,” the article quotes Warren as saying. “Not only are they operating in violation of the state gambling law but in serious ways constitute public nuisances. I’m satisfied that a substantial portion of the relief funds goes through betting windows at dog tracks rather than into the mouths of children the money is supposed to feed.”

Warren sent agents to raid the dog tracks and all of them were shut down by 1939, with the El Cerrito Kennel Club being the last to close. That same year, “Big Bill” Pechart was forced to close his Rancho casino.

For a time, the land surrounding the track was used as a trailer park for wartime workers. According to an Oct. 20, 2015 article in the Mercury News, El Cerrito High School’s “first varsity football team played in 1943, and home games were at the former El Cerrito Kennel Club dog racing track on the historic Castro rancho property where El Cerrito Plaza stands today. The field was leased from racetrack owner Black Jack Jerome, who had turned down a similar request from Albany High School before World War II to lease the site for school sports after the racetrack was closed by the state in January of 1939.

“The racetrack grounds had no turf, meaning the first El Cerrito Gaucho teams had to play home football on a field of dirt and rocks. It did, however, provide a nice big grandstand for the fans.”

The grandstand was finally torn down on May 10, 1948. The site later became the home of El Cerrito Motor Movies, a drive-in theater.

For several years starting in 1943, the El Cerrito High School Gauchos football team played their home games in the abandoned infield of the dog track. Trailers housing workers who moved here to work in war industries can be seen in the background. EC Historical Society collection.