The End of The Castro Adobe

Two 15-year-old boys admitted setting the fire that destroyed the Castro Adobe in 1956. The fire occurred the night before a hearing on whether to preserve the historic building or level it to clear land for the planned El Cerrito Plaza shopping center.

This is an excerpt from “The Adobe at Cerrito Creek,” a 12-page history of the Castro Adobe, from its beginnings in 1837 to its destruction by arsonists in 1956, written for the El Cerrito Historical Society in 1975 by El Cerrito Fire Department Chief Inspector Earl Scarbough. This section describes the intentional burning of the structures, paving the way for development of the El Cerrito Plaza shopping center.

The end of Rancho San Pablo as a gambling casino came during World War II. A dog racing track that flourished at the back of the casino closed, and the property was converted into a mobile home court that housed thousands of shipyard 1vorkers. "Big Bill" moved on to Reno where he became a pit boss at the Mapes Hotel and in 1965 died of a heart attack. When the lights of the casino were turned off for the last time the adobe once more returned to solitude. After the war the mobile homes moved out and a drive-in movie theater was erected on the site. The old hacienda remained vacant through the years. Automobiles were driven across and parked over the tiny cemetery. Juveniles, most of them high school boys, often prowled the premises. Many windows, some of them heavily barred, had been broken and all of the valuables had long been removed from the adobe. The interior of the structure became littered with debris and fallen timbers.

In 1955, the site was purchased for the construction of the El Cerrito Plaza Shopping Center by the Albert Lovett Company of Berkeley from the estate of Julia B. Galpin, daughter of Don Victor.

Immediately, considerable controversy developed over whether the adobe could be presserved as a historic monument or would be demolished for the multi-million dollar shopping center. El Cerrito City Councilman Leo Armstrong had sought to introduce a resolution that would keep the adobe as a permanent structure in El Cerrito. Paul Hammarberg, architect for the Albert Lovett Company, started a survey to determine the feasibility of moving the old buildings intact or leaving them where they were as a monument to the county's first family.

Then, on the evening of April 20th, 1956, two off-duty El Cerrito firemen, Lieutenant William Dugan and fireman James Sadler, were at the adjacent El Cerrito Motor Movies with their families. Dugan, visiting a friend in the projection room, noticed sparks flying out of the adobe, then came billowing black clouds of smoke. Sadler, who had also seen the fire starting to erupt into the night, raced to the projection room to call the fire department. He and Dugan ran to the adobe and into the patio area to determine if anyone was inside the structure. So rapidly did the intense fire sweep through the old buildings that Dugan and Sadler barely escaped. Numerous El Cerrito residents in the downtown and hill area noticed the sky beginning to turn a brick red and flooded the fire department with·calls. When El Cerrito's first engines arrived under the command of newly appointed Fire Chief Edward Herman, the entire inside of the building was on fire and huge orange-red flames leaped a hundred feet into the night sky.

Chief Herman immediately called all El Cerrito fire apparatus and all off duty firemen into the fire as well as apparatus and men from the neighboring fire department in Albany. Fire engines from Berkeley and Kensington manned El Cerrito fire houses for the protection of the rest of the city.

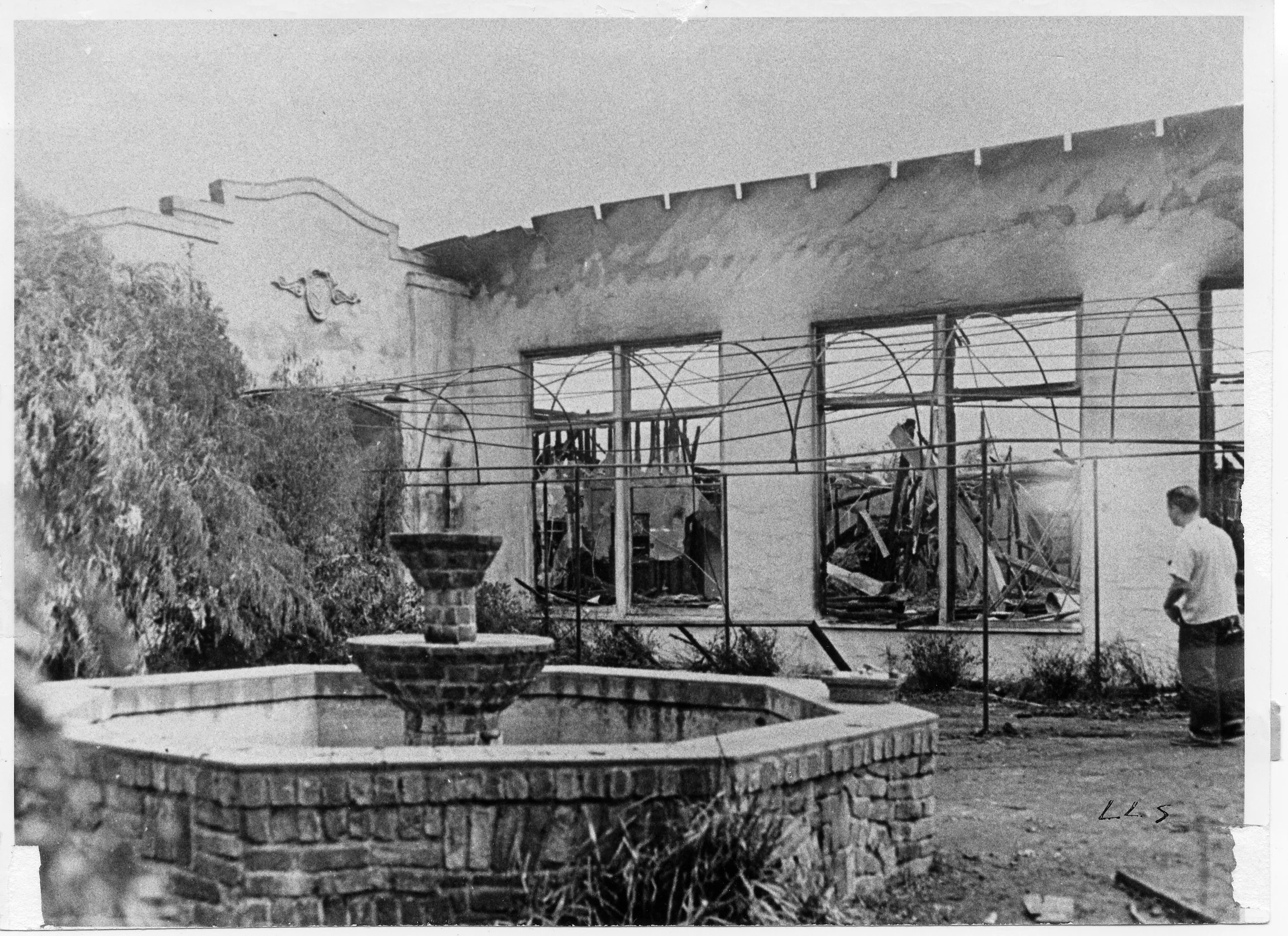

Soon after the fire started, electricity to some of the downtown districts was shut off. Flames and rolling smoke filled the air providing the only immediate light to the area and attracting a crowd of thousands. Traffic was blocked for nearly two hours on San Pablo Avenue as the curious flocked to the scene. Engines laid approximately 6,000 feet of fire hose and firefighters fought to gain control of the blaze. The barred windows and crumbling walls made it difficult for firemen to get close to many parts of the building. Then, after a three-hour battle, the flames flickered and died under the deluge of water, and, as the flames died, so died the last landmark of the county's first Mexican rancho.

In the predawn hours as Fire Chief Herman prowled the smoldering ruins of the adobe, he became acutely aware of the smell of kerosene. The fire had been set.

Spearheading an investigation was El Cerrito Police Lieutenant Homer Johnson. After checking every available scrap of information, the veteran officer found himself at a dead end. It was not until four months later that the police department received an anonymous phone call revealing the responsibles’ names. Within a few days two teenage suspects were administered a polygraph examination.

And after questioning, the two 15-year-olds admitted purchasing 10 cents worth of kerosene in a half gallon can at a gas station at Bay View and San Pablo Avenue. Both youths then walked south on San Pablo Avenue approximately two miles until they reached the adobe. Entering the abandoned building, they poured the contents of the can through the rooms, and igniting a paper bag, threw the flaming bag into the puddles of kerosene. Fleeing the building, both boys entered the Cerrito Theater where they were overheard talking about the fire approximately one-half hour before the firemen saw the flames from the motor movies and turned in the alarm.

When asked their reason for setting the fire, the lads related, "The city was dead on Friday nights and they wanted a little excitement. Besides, I heard somebody say they were going to tear the place down. I decided to get rid of the place -- burn it down." Later in the day, officers took the boys back to the scene of the fire. They pointed out where they

had spilled the kerosene, and searching the area, located the can in which they had carried the flammable. The two youths were charged with arson and turned over to Contra Costa County Probation authorities.

In the weeks that followed, workmen and bulldozers wrote the final chapter of the Rancho San Pablo as they cleared away crumbling adobe walls and leveled the little knoll to accommodate a facility of another era -- a modern shopping center. Perhaps today, one may be forgiven if, when driving along San Pablo Avenue between El Cerrito and San Pablo, and amid the rows of homes and shops, stops for a moment and breathes a nostalgic sigh for the days when the Castro's rode across the hills through leagues of flowing grass tending their grazing herds.

Although parts of the masonry and thick adobe walls remained after the fire, the ruins were later cleared to make way for the shopping center.

Excerpted from “The Adobe at Cerrito Creek,” a 12-page history of the Castro Adobe. Read the entirety here (PDF file).